WURA & PQR WTF

Understand Work Unit Routing Analysis (WURA) by starting with its predecessor: Product-Quantity Routing (PQR) analysis.

You’ll find PQR analysis used in settings where there are a lot of small-batch custom orders. Imagine a print shop, paint shop, or light manufacturer that has to set up and configure workspaces and equipment for a specific run of work, ship those off, and then re-set and re-configure things for the next, different, run; e.g. an environment where a lot of things are always different, and a lot of other things are always the same. Knowing which products (intermediate, scrap, and final) (P) are being made, and in what quantities (Q), as they are routed (R) across the shop then becomes the basis for various insights.

WURA extended this analytical approach to clinical settings, and from there into other types of work—including the hopelessly computer-afflicted work I get involved in. To call the products of labor “work units” (WU) upon which one performs a similar routing analysis (RA) is a long walk to get to the WURA acronym. My experience has been that some people have heard of PQR, and others WURA, and the happiest people have heard of neither. So I mention both acronyms and their relationship.

When you might use it

Whatever you call it—or even if you don’t call it anything, but just do it—WURA is a great fit for low-batch, moderate complexity, highly variable work. If I hear something like “we don’t have a process” or “every <instance> is different” I start to wonder if WURA might be a good format to start building into.

A few instances where I have used it

- To document various ways projects were getting approved inside a corporation while bypassing the ”official” approvals mechanism.

- To discern how a real estate company prepares distressed properties for sale at auction across various geographies, property conditions, etc.

- To understand internal billing and invoicing procedures for a professional services firm across its various lines of business and types of customers.

- To see where decision-making failed to occur inside a corporate operations group.

How to run WURA

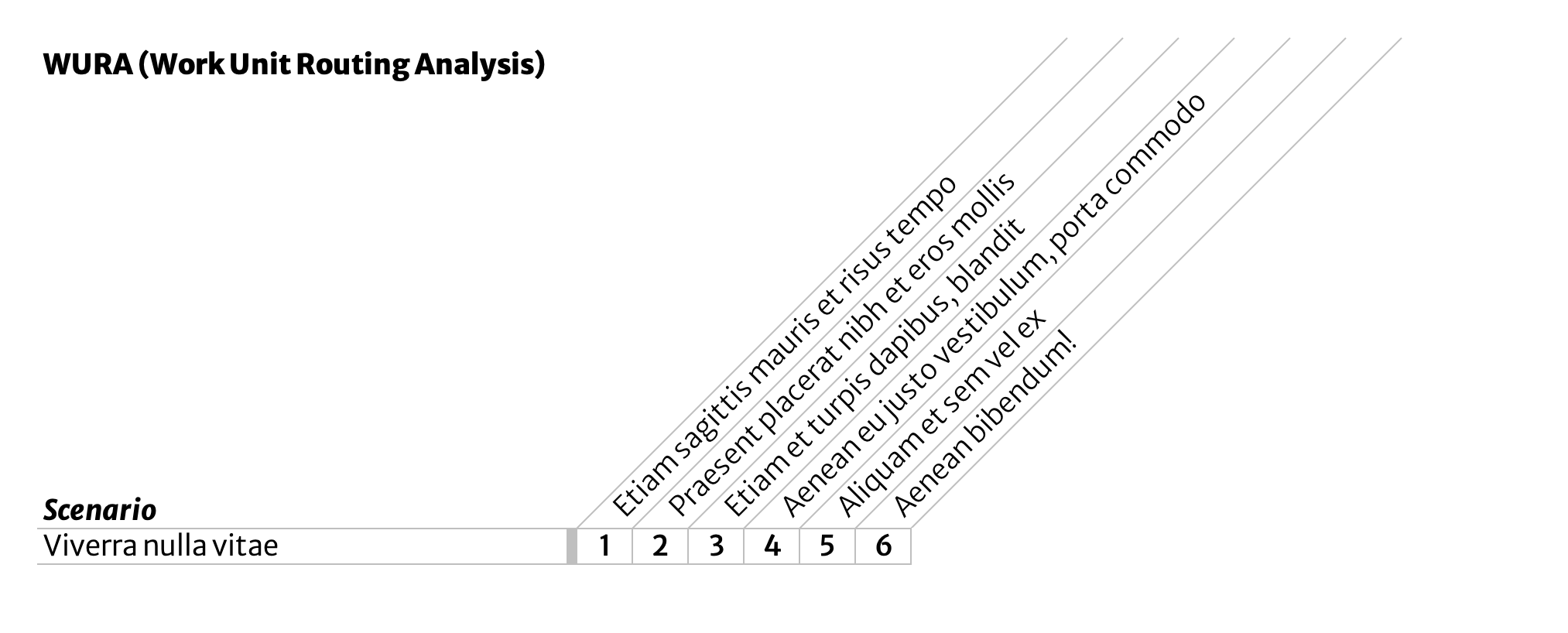

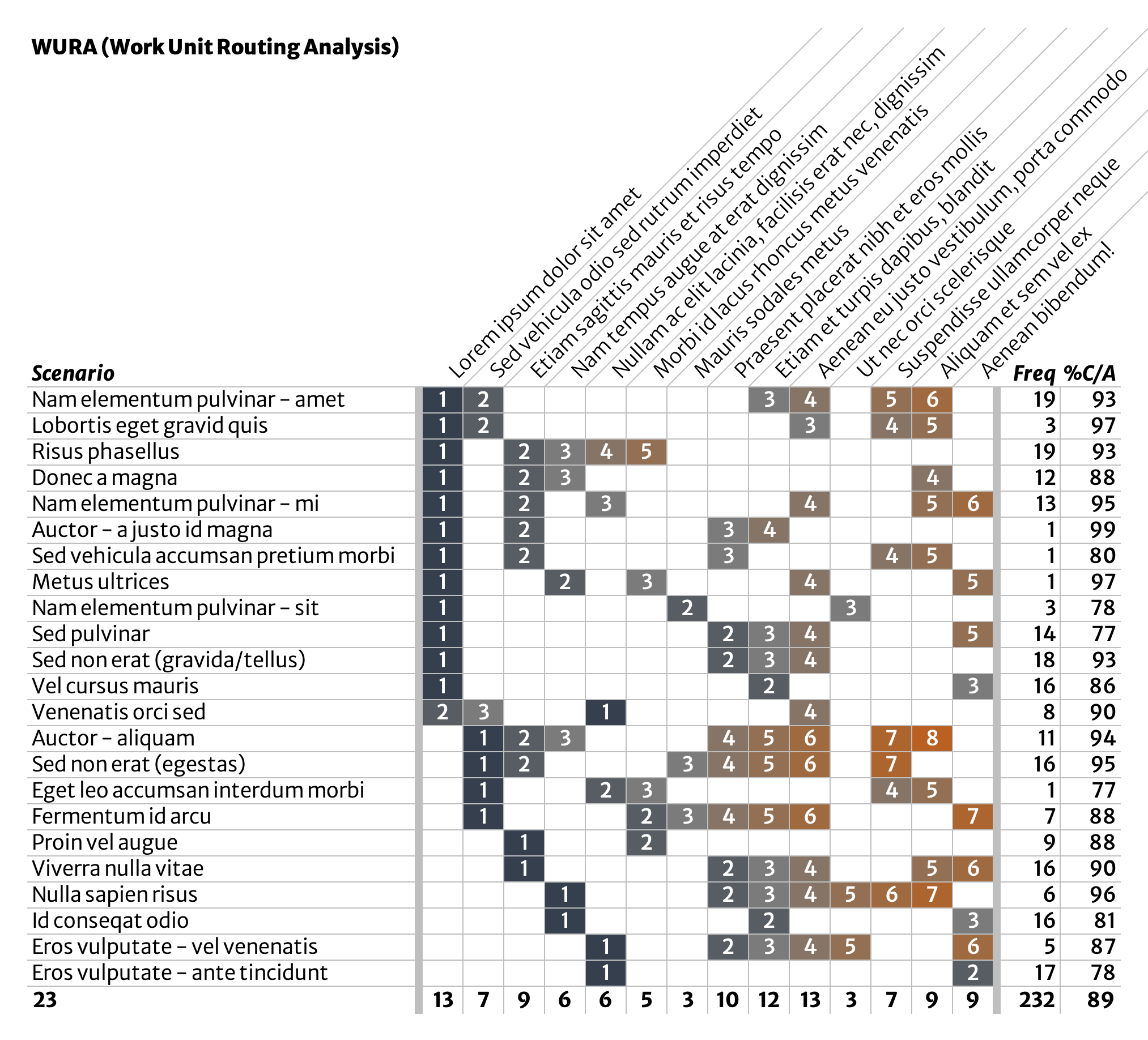

Describe a single scenario

First, document a single scenario in a single row in a data table. Major process steps are numbered 1-6 and each given a short but descriptive name. Easiest way is to follow a single “work unit” around and see what people do. Go to the place of work, job shadow, all that. Don’t get into exceptions handling or alternate scenarios (these will get their own rows later).

Any methods encountered elsewhere for identifying process steps will work here. Look for transitions, hand-offs, notifications, etc.

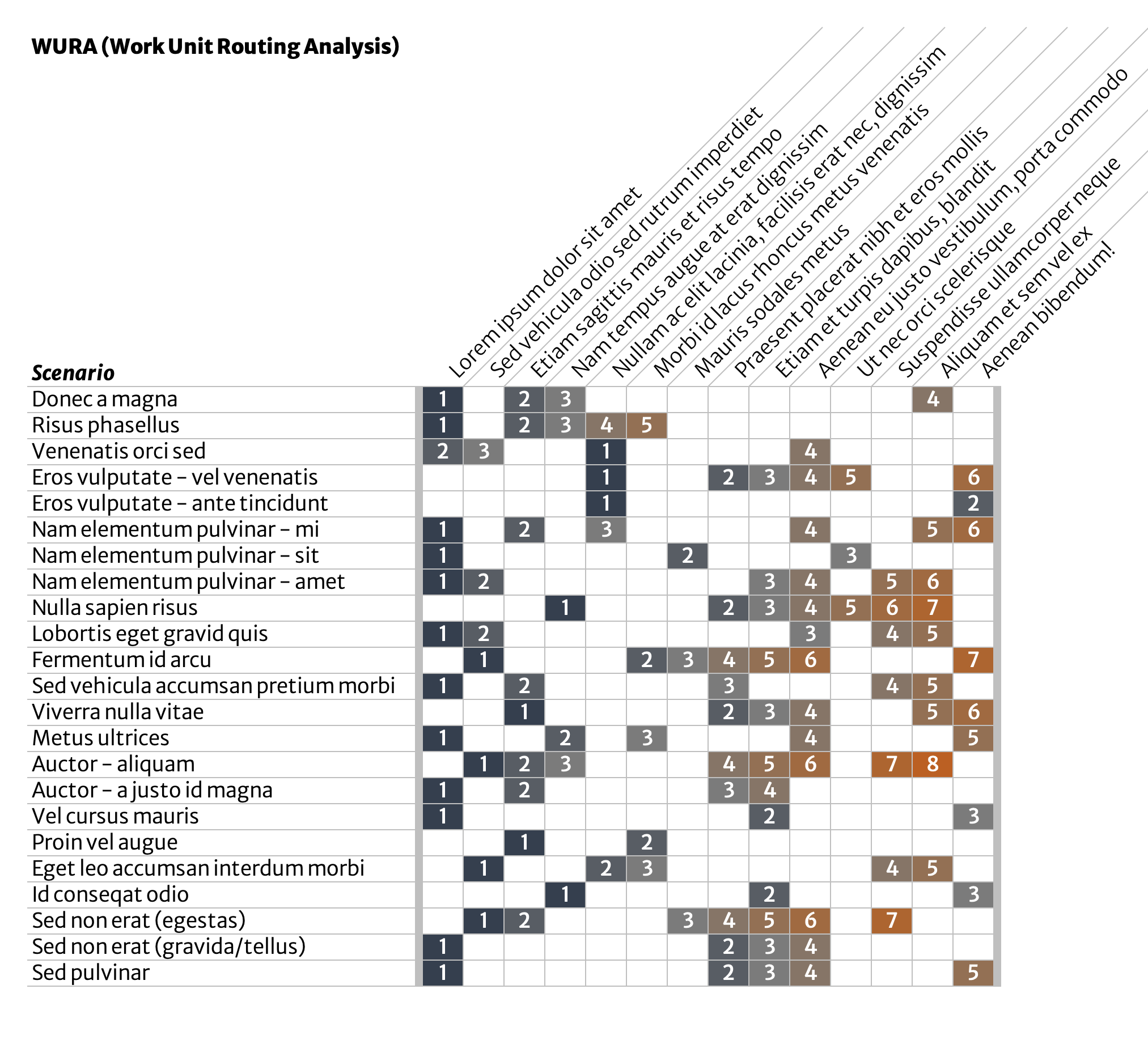

Document additional scenarios

Next, document as many additional scenarios as you encounter, using the same format. Number process steps in sequence. Add new process steps as you see them. This list is totally unordered at this point. Keep adding exhaustively.

Exceptions, special cases, rush jobs, undisussables—each get their own row.

Seek to keep process steps at approximately the same level of detail. It is also OK to split, combine, and rearrange in order to match what is actually happening out there.

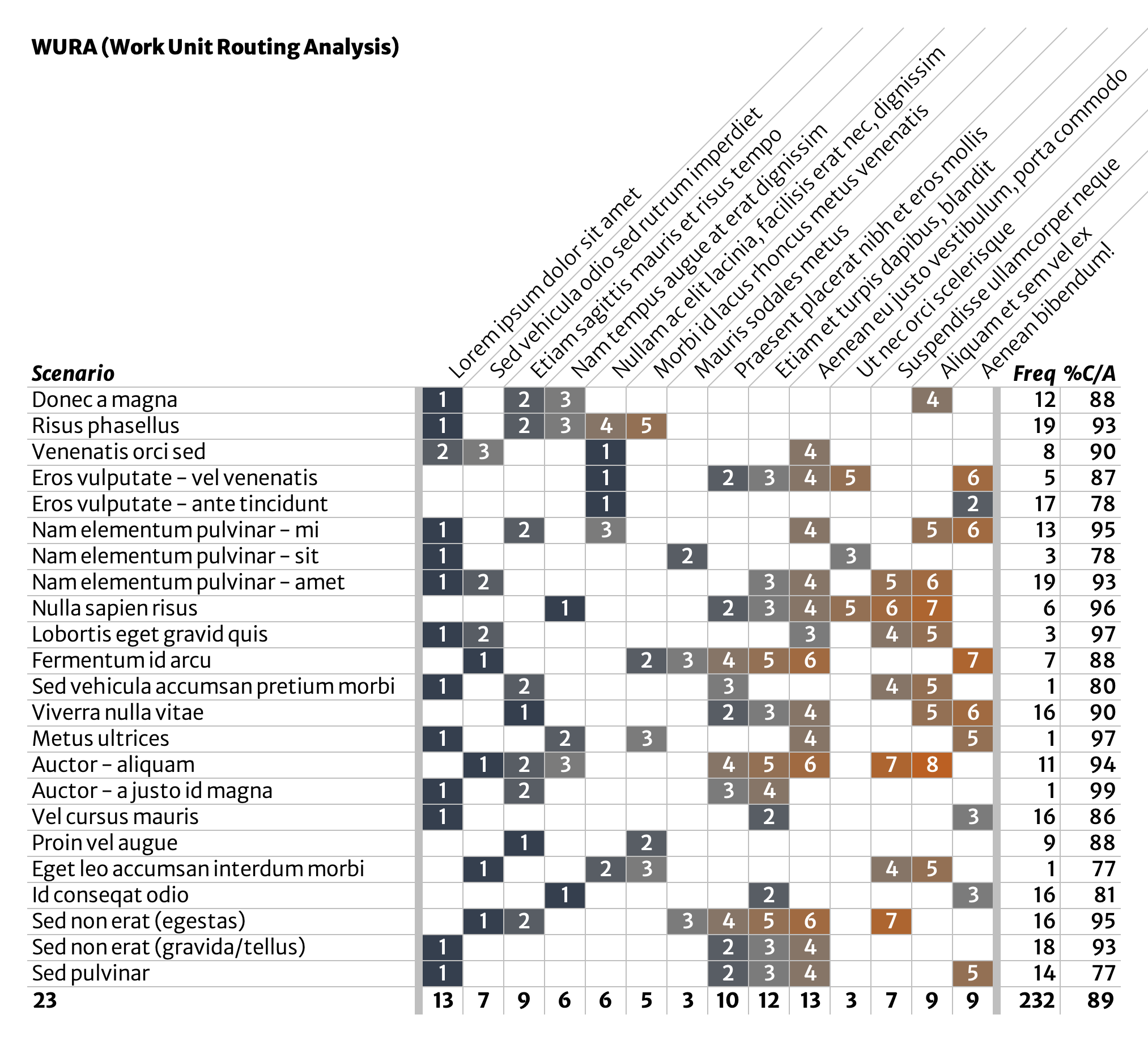

Annotate with frequency & quality data

At some point you will exhaust scenarios people can show you or that can be observed. They may say that “every <instance> is different” but the finite length of this scenarios list indicates otherwise, at least when viewed from a certain level of abstraction.

To the extent possible, annotate the list with a few data points for each scenario. What’s important to measure? Use your best judgement, tempered by availability of data. Good starting points are those shown here:

- Frequency—# of “work units” produced via this scenario over a certain term (1 month, 1 year, etc.)

- %C/A—percent complete & accurate; this is a percentage of work items that are both complete (nothing missing or broken) and accurate (correct) as they exit each scenario.

- Not shown here, but much more powerful, is to also measure %C/A for each process steps—measuring how often work items ENTER the given process step without quality issues.

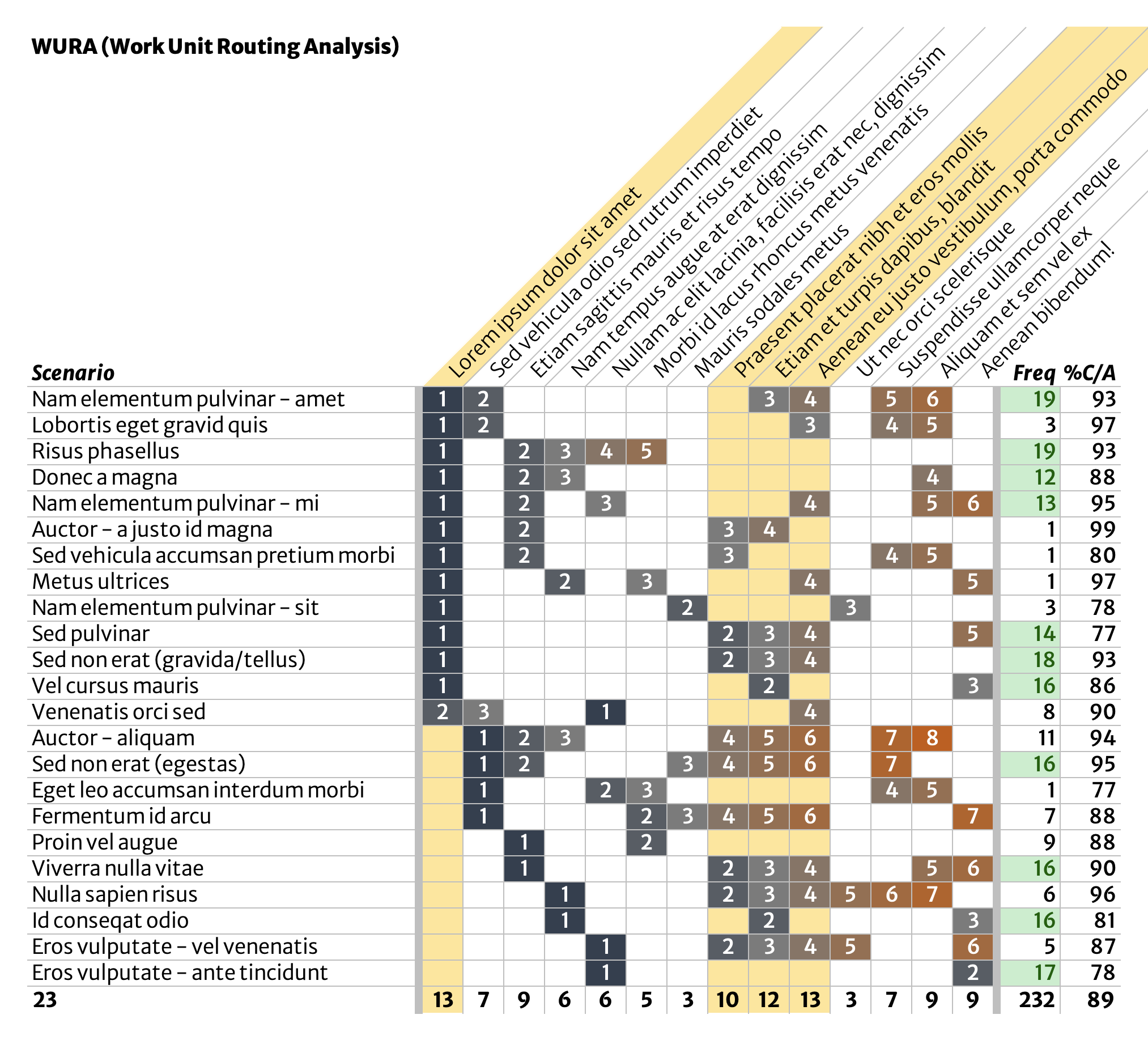

Initial analysis—what do scenarios have in common?

Sort and slice. In this example, about half of the scenarios (and a majority of the overall volume) begin with the same process step (“Lorem ipsum…”). Extend that to also include the “Sed vehicula” process step and you’ve identified where most work starts, even though “we don’t have a process”, etc.

You might also notice a little set of three process steps, highlighted below, that are a feature of several scenarios. What might these have in common? What’s the case for scenarios relying on one or two, but not all three, of these process steps?

Lines of questioning like this can help you notice possibilities for simplifying or standardizing work in beneficial ways.

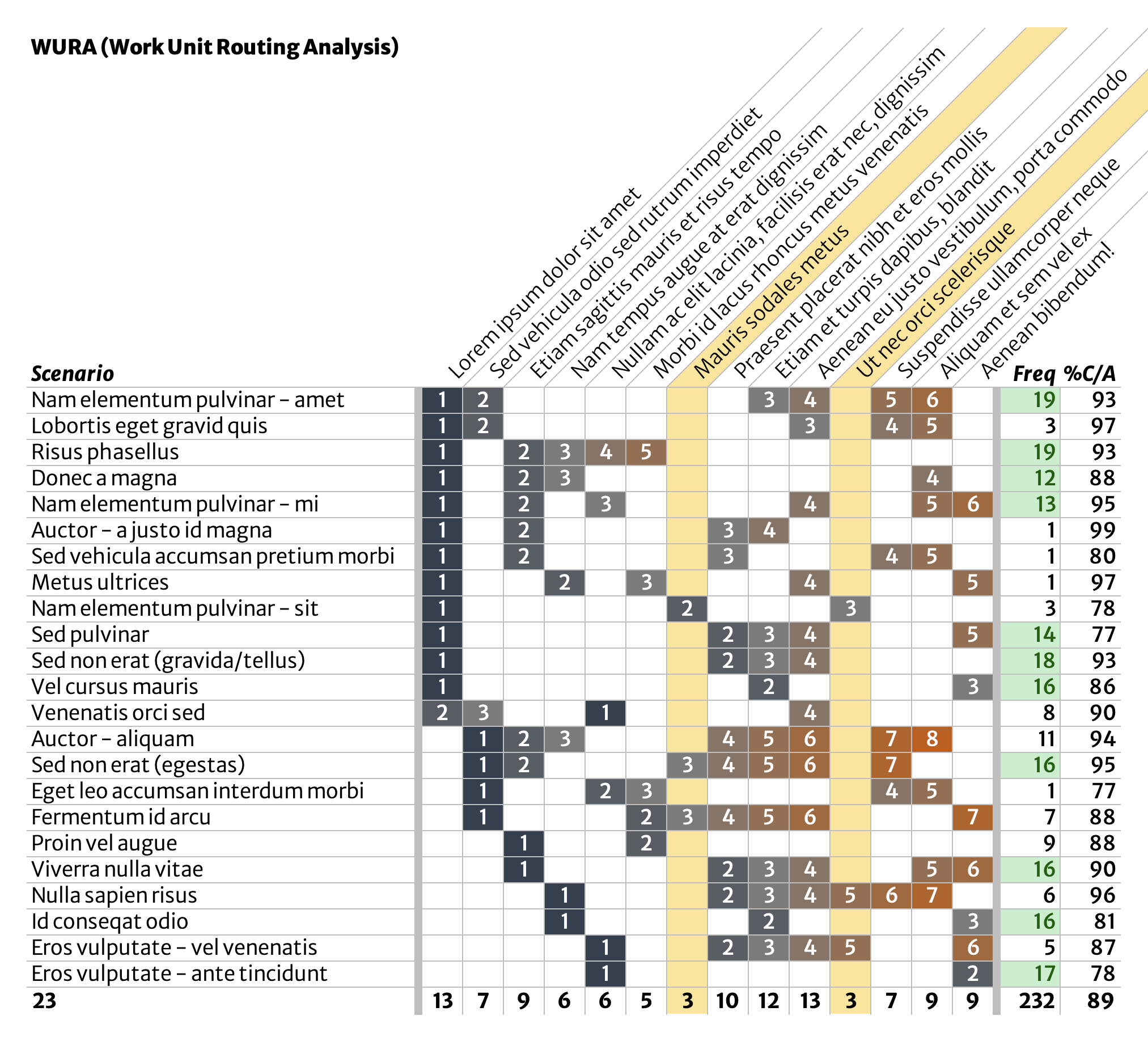

Initial analysis—clean up outliers

Another very quick analysis is to look for the true outliers. The highlighted process steps below appear only in a handful of scenarios, and only one of those scenarios (“Sed non erat…”) arises at a decent frequency. These process steps might be eliminated entirely, possibly even by adjusting or removing the scenarios they are a part of.

Anything that can be removed entirely is a treasure.

Possibilities for further analysis

- Determine which process steps contribute most to overall volume (for example, the simplified visuals and column totals in this example are misleading if you were to guess at this mostly visually).

- Isolate process steps where errors are produced and build in quality.

- Measure worker sentiment/happiness with each scenario.

- Group scenarios into “process families” based on their similarities, and then do continuous improvement at the “process family” that might otherwise be too fine-grained for management or scheduling to allow.

- For example, folks who love to do value stream mapping might do so with one “process family” at a time (please don’t do this).