Online reading

At the beginning of October, I felt afraid and stagnant. Let’s start there.

On fear—Bill McKibben writing on October 9, a few hours before Hurricane Milton hit Florida, a month before a consequential and confusing US election:

The fear of a planet where the old rules no longer hold is the ultimate fear—because then how do you even think about the future? And that’s as true as politics as it is in meteorology.

And stagnation—revisiting an essay by Mandy Brown:

Growth occurs in intervals: there are times of growth, and there are times of non-growth. The latter isn’t a failure so much as a necessary period of rest. Dormancy isn’t stagnant; it’s potentiating. It’s patient. If you’ve grown a lot in the past however many months or years and now feel that growth coming to a close, don’t fret right away. Wait. Reflect on what you’ve learned. Look for signs of spring. Move to where there’s water, if you need to.

While all this is going on, I keep busy at work. In my facilitation practice, I help people uncover their priorities and values and then, within those new structures, gleefully deliberate and take skillful action.

Here’s Chelsea Troy on group deliberation:

The perspectives that matter the most in decision-making, are precisely those perspectives that typically get excluded from participation in the thing we’re making decisions about. … When you’re facilitating a decision that’s going to have a wide impact crater, you have to go find precisely the interests that often aren’t represented for this kind of decision—who don’t even get a vote—or who always lose the vote.

These parties frequently have concerns that the vote completely fails to address. Recall from the last post that we introduced two categories of metric: optimizing metrics (where we need to find the best solution) and satisficing metrics (where we need a minimum acceptable solution). Marginalized concerns in decision-making often should be preliminary satisficing metrics: they should be table stakes, because they determine who gets to participate at all, rather than a slight preference.

By the way, the best method I know of for designing something new while ensuring that everybody’s minimum specs (what Troy calls table stakes) are identified, met, and exceeded is set-based design.

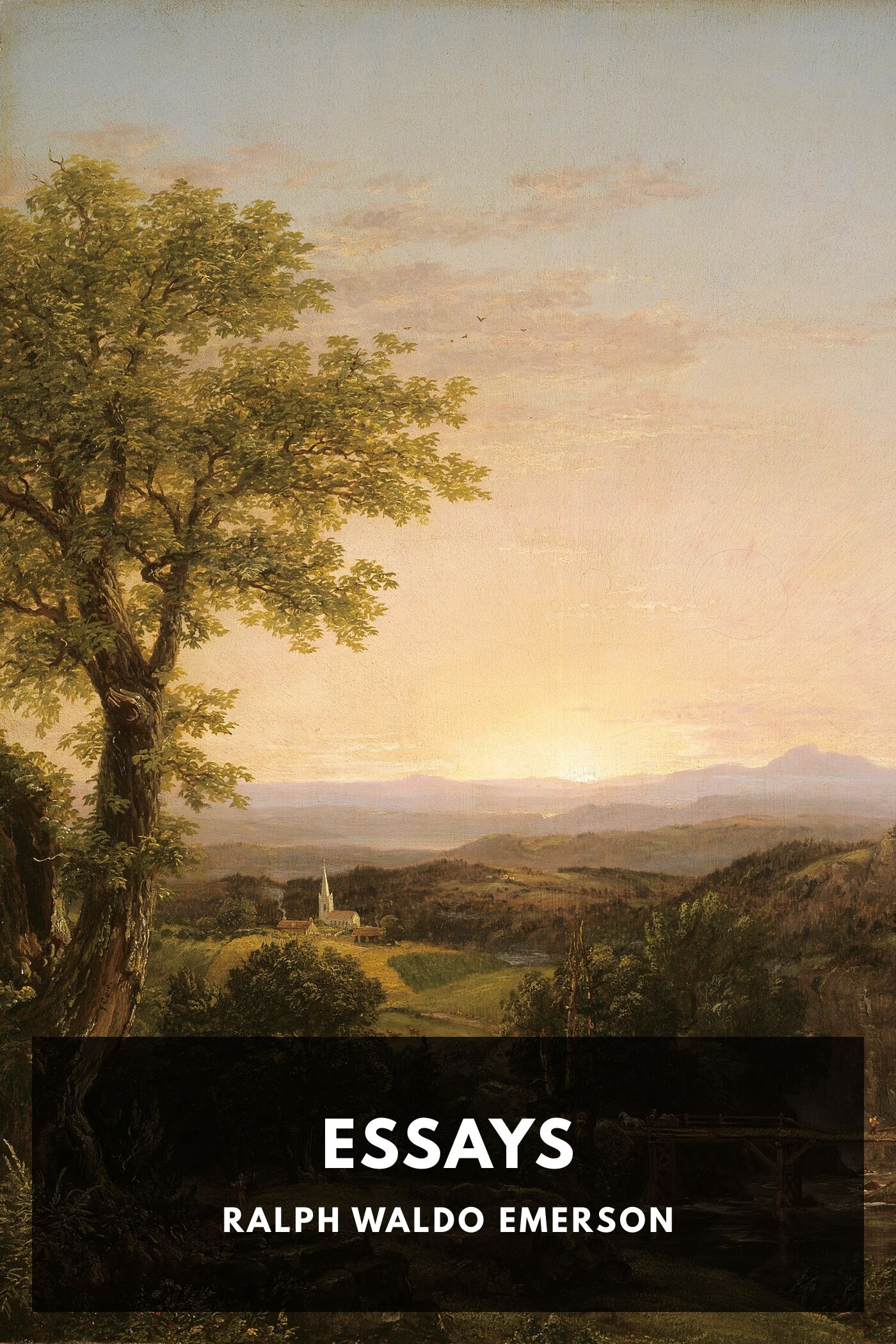

Books

Standard Ebooks has produced a beautifully formatted, freely available ebook edition of Mary Parker Follett’s “The New State” from 1919. Yes, it’s over a hundred years old. And it remains a readable, engaging look into group formation, deliberation, and decision-making.

There are a million ideas in Follett’s writing. One that sticks with me is this:

Unity, not uniformity, must be our aim. We attain unity only through variety. Differences must be integrated, not annihilated, nor absorbed.

And finally, my friend Devon Persing’s book, “The Accessibility Operations Guidebook,” is out. She writes:

This book is two things. The first is a crash course in frameworks and ways of thinking from fields like information science, organizational theory, and DEI. The second is a walkthrough of building and operationalizing sustainable, data-driven accessibility programming.

Even though I don’t work in the digital accessibility field, I got a lot of practical information out of the back half of this book (chapters 10-14). Devon has great advice on org design + operations challenges, like:

- whether to couch an offering as a service and/or a program,

- ways to use or commission information, and

- tips on goal-setting in service of group decision-making.

Learn more about the book and buy a copy (if purchasing on Payhip, use coupon code PUMPKINTOAG for 25% off):

Gratitude

I entered October feeling afraid and stagnant: worried about the climate, about the US elections, about a dozen wars around the globe, about every horror ongoing and unabated and by this point nearly forgotten, about the health and wellbeing of my immediate family.

Thank you to Liana and our children and various folks at work and kind friends in town and around the globe, each of whom supported me in going on silent retreat for a week.

This month, that community of silence made all the difference.

So as we leave October, I’m still afraid. But I am also ready. I cling to these lines from Yu Xuanji (the 9th-century poet/courtesan/Daoist nun):

Water fits itself to the vessel that contains it.

Clouds drift artlessly, not thinking of return.

Spring breezes bear sorrow over the Chu river at dusk:

separated from the flock, a lone duck is flying.

The season has turned here in Tacoma. Rainfall and drifting clouds. I look out the window for the reminders I need: to fit myself to this vessel. To drift imperfectly and without thinking of return. To engage and assist and participate as much and as long as I can. To keep flying, in darkness.