Putting together a coherent, useful strategy for a group is hard.

- When strategy gets too complicated, intelligibility goes out the window. Nobody will adhere to a strategy they can’t remember. But…

- When strategy is too simple, it’s merely a container for people to toss their assumptions and pet projects into.

- And often a group is required to keep a strategy document in order to unlock funding, etc., even though nobody is excited to create it or use it.

Now—as a consultant—I’ve been called upon to create strategic plans and the like that I knew were going to collect dust. The complete and immediate uselessness of the strategy was a foregone conclusion. I’m not proud to say it, but I’ve flown across the country, eaten lousy hotel breakfasts with those weird runny eggs, and hosted elaborate multi-day sessions all in order to generate complicated, detailed strategic plans that nobody wanted, nobody used, and ultimately helped no-one. What a waste!

A couple years ago, in an effort to never do that again, I hit the books. Here’s what I found—it’s my go-to method to help a group of people generate and explain their strategy.

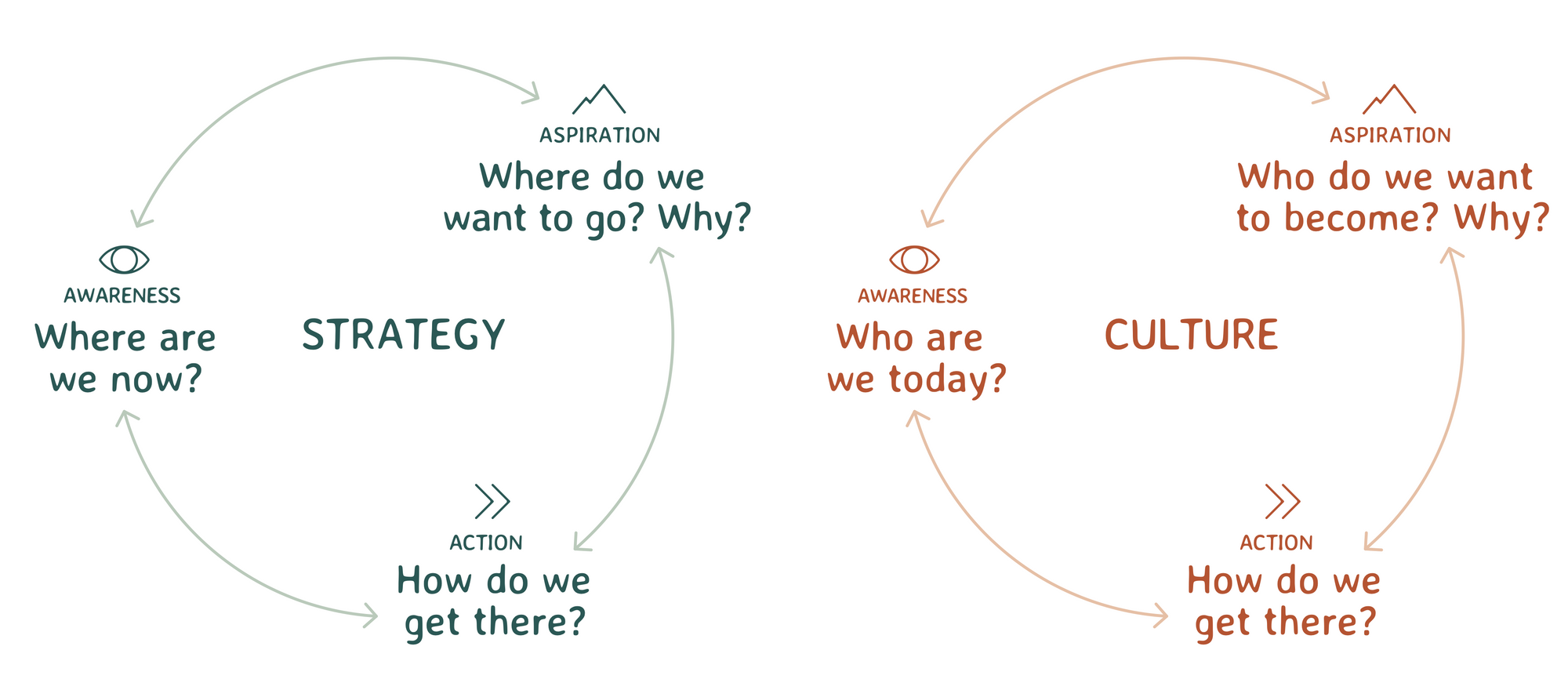

The Strategy/Culture Bicycle:

A wheel for Strategy. A wheel for Culture. And three questions on each wheel which can produce real, meaningful, shared understanding of a group’s intent. When guided by an attentive facilitator, you can get it done in an hour or two and create something amazing. (A detailed facilitator’s guide is available. It is excellent.)

Not part of the Strategy/Culture Bicycle: setting goals, establishing performance measurement, planning. But each of these are way easier to do once there’s consensus on thoughtful answers to these questions.

In my experience, Strategy/Culture Bicycle works for three reasons:

- It cuts directly to the big questions without getting mired in a bunch of the inventory-making throat-clearing, fussing about contingency, or working backwards from preferred / “management-approved” actions that overtake many strategy efforts.

- The inquiry-based affinity mapping that generates a Bicycle prevents any one person from defining strategy in a way that others can’t, or won’t, support. Autocracy is incoherent.

- The Bicycle reminds us that a group needs to have both strategy and culture operating in parallel. Too many strategy documents exist in a timeless void, severed from the people and ways of being which might realize that strategy.

The Strategy/Culture Bicycle was created by Eugene Eric Kim and Amy Wu. I’m grateful for it. It’s in the public domain. Go for it: start with the web-based intro, then move onto the detailed instructions.

And here’s a secret: if you want to figure out who to become and where to go, you can prepare a Bicycle for yourself, by yourself. No lousy hotel breakfast required.