A passage from Jerry Weinberg’s The Secrets of Consulting:

Your ideal form of influence is first to help people see their world more clearly, and then to let them decide what to do next. Your methods of working are always open for display and discussion with your clients. Your primary tool is merely being the person you are, so your most powerful method of helping other people is to help yourself.

I first read Jerry Weinberg around 15 years ago, at a time when I was comfortable working as an independent consultant, but remained deeply uncomfortable with existing in the world as a human being. I wasn’t yet ready to take seriously the projects of caring for myself, or for others, or understanding what it was like to be a person.

That passage really stuck with me. Let’s read it together.

“Your ideal form of influence is first to help people see their world more clearly, and then to let them decide what to do next.”

The best job description for my kind of work that I’ve ever seen. It opens questions like:

- Which people? Who is excluded yet should be included?

- What constitutes their world?

- How do they make that world intelligible to themselves or to others?

- How might they (as a group) produce explanations, find consensus, or make a decision and stick to it?

“Your methods of working are always open for display and discussion with your clients.”

If we’ve worked together, you know what this is like. The garage door is up, where somebody is always making a mess and then cleaning it up so it shines.

As a consultant, I will come and I will go. After I’m gone, I hope some of the methods of working I demonstrated might be retained. This is why I enjoy cycling through approaches, methods, and techniques. At the start of an activity, neither you nor I know what will work best, but we can hope to uncover it together.

“Your primary tool is merely being the person you are, so your most powerful method of helping other people is to help yourself.”

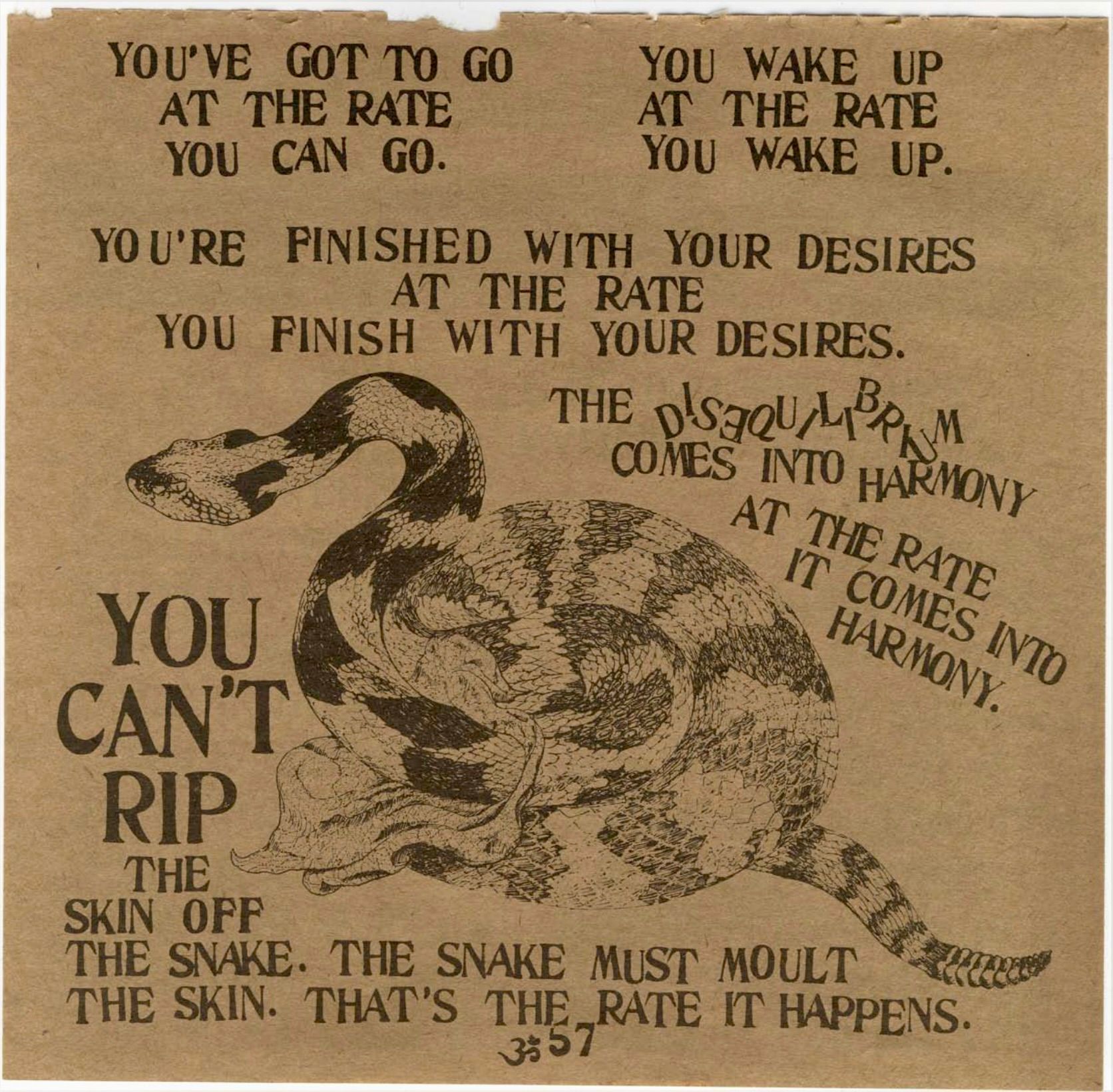

It’s only in the last few years that I’ve come to recognize myself as an object truly capable of being helped, much less being worth the effort. Weinberg’s words gave me an important, early reason, which I now see as evidence of how deeply damaged I was (and still am) as a subject of capitalism. But that’s fine: you’ve got to go at the rate you can go.

These days, I work to keep things quiet in my head, so I can listen carefully to others. I sit still on my cushion so I can get up and move skillfully. I practice kindness so I can act kindly. Would it be better if I had come to these on my own, or earlier? Certainly. But I am grateful they came when they did.

No two go by one way; this one was mine.

Thanks, Jerry.