Most continuous improvement events fail. I am curious why.

Today’s reason for failure is disconnectedness.

Earlier in my consulting days, I’d say “yes” to any one-off continuous improvement project that came my way—things like sitting with a new group to do an A3, or hosting a half-day event. I figured that if folks had a problem to fix and a sponsor willing to let them to work things out, it couldn’t possibly hurt, and might even help.

The events themselves were always fun. It’s fun to gather people together for a few hours and enable them to learn from each another in surprising ways. It’s fun to go where the work gets done and notice weird things happening there, to fix problems, to enjoy snacks and coffee and the company of others.

But I became dissatisfied with the success rate. Here’s what happened:

- Sometimes the events worked.

Ideas arose, people made changes, the changes stuck. - Sometimes they sort of worked.

Maybe there was a short-term change for the better, but then things reverted back to the way they were before. - Sometimes they didn’t work at all.

And this is the problem:

Everything is interdependent. We’re all connected. To pick up a particular piece of the muddle and draw a tidy rectangle around it and work on it in isolation is to miss nearly everything.

The ideal

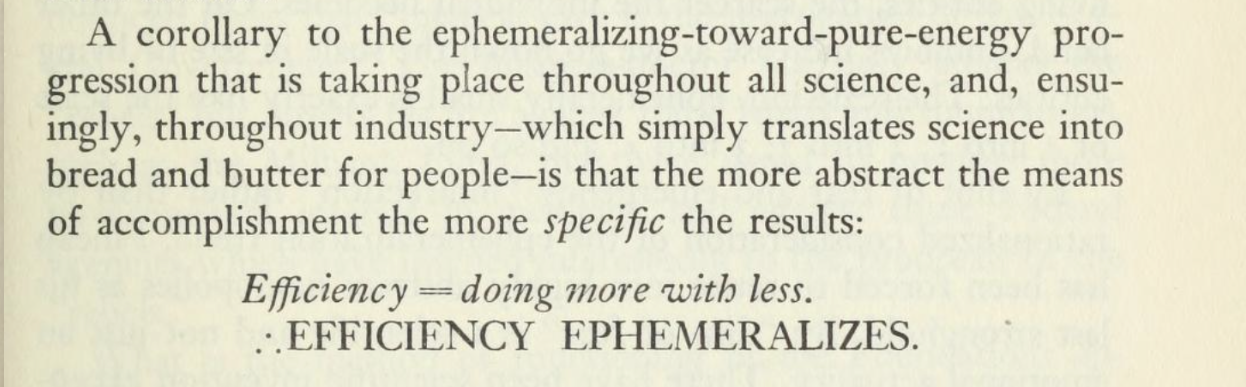

Ideally, specific lean interventions are part of the daily work. In one classic formulation: Work = Job + Kaizen. Ideally, they are supported by leadership through a management system. Ideally, they are broadly understood and intelligible by passersby within and without the organization.

The strongly OK

But if that ideal condition does not exist (it very rarely does), now what? Should you say ‘no’ to everything? Or say ‘yes’ to everything and hope that some of it sticks?

My move—and it’s a pragmatic, or ‘strongly OK’ move—is to connect continuous improvement activities to something that is already valued and understood by the organization. This connection is what you can establish at the outset, and cling to after an event is over.

It’s the hook you hang the continuous improvement hat on.

So, in a ‘strongly OK’ world, try to connect continuous improvement work to (from most to least preferred):

- Safety, quality, or satisfaction—for customers, employees, or suppliers. Must be quantifiable.

- Business value—show how the current condition is costing the company money. Must be quantifiable, and something that is already familiar and meaningful to people.

- A executive’s important initiative. But initiatives don’t last long, even the important ones, and some people will not be on board. This is a weaker connection than it might seem.

- The organization’s mission, vision, or strategic plan. These things probably exist under a thick layer of dust. They’ll motivate continuous improvement to the same extent they motivate anything else in the organization—very little. If your organization is the exception to this rule, then move this up to the top of the list.

By connecting a continuous improvement event to one of these, and making that connection strong and broadly communicated, you increase the odds that the event—or its results—won’t float away.