- Do the very first thing someone suggests. Commit as many resources to it as possible: we’re all in on the new approach, no matter what.

- Do the very first thing someone suggests. Do not commit anything at all to the solution: we’re doing more with less.

- Don’t waste valuable time identifying or understanding the problem. As people wheel and mill around and solve for slightly different things, it’ll boost creativity or some damned thing.

- Fix something upstream without looking downstream.

- Fix something downstream without looking upstream.

- Have you considered a reorg?

- Don’t talk to customers. Of course you know who they are and what they want. This goes without saying.

- Whatever else you do, put a thing on the timeline called “evaluate & adjust” or similar. Schedule it to be held in 6 months’ time. By then, everyone will have forgotten.

Improve Something Today

Posts on page 6

8 ways to push a problem around (without fixing it)

A “to not do” list.

Monthly links & notes for January 2024

An obituary, a few readings, a book & an online course.

Online reading

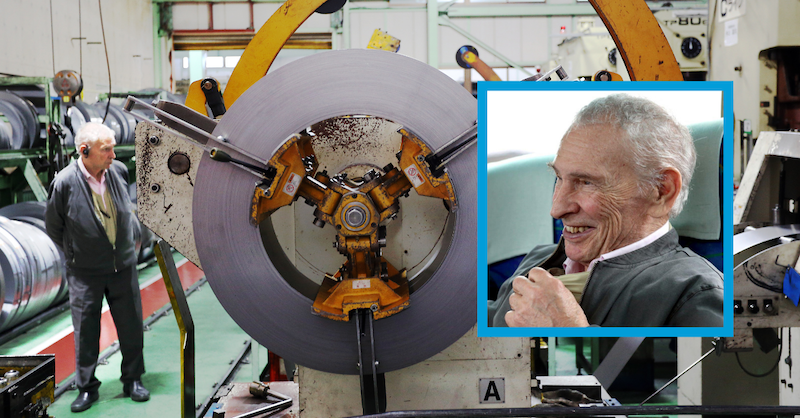

This month I’m remembering the life and work of David Mann, who passed away in late December. He was one of those Michigan lean people who had a big effect on me, although I only met him once, in passing, at a conference. That big effect was through his book Creating a Lean Culture: Tools to Sustain Lean Conversions. It helped me and Andre more skillfully support a couple of lean projects back in the day, including the one where I saw that when it all worked, it really worked. So, thanks, David.

Ruth Malan shared a free systems thinking (“systems seeing”) month-long daily journal. She encourages you to work through it, spending ~15 minutes on each daily exercise:

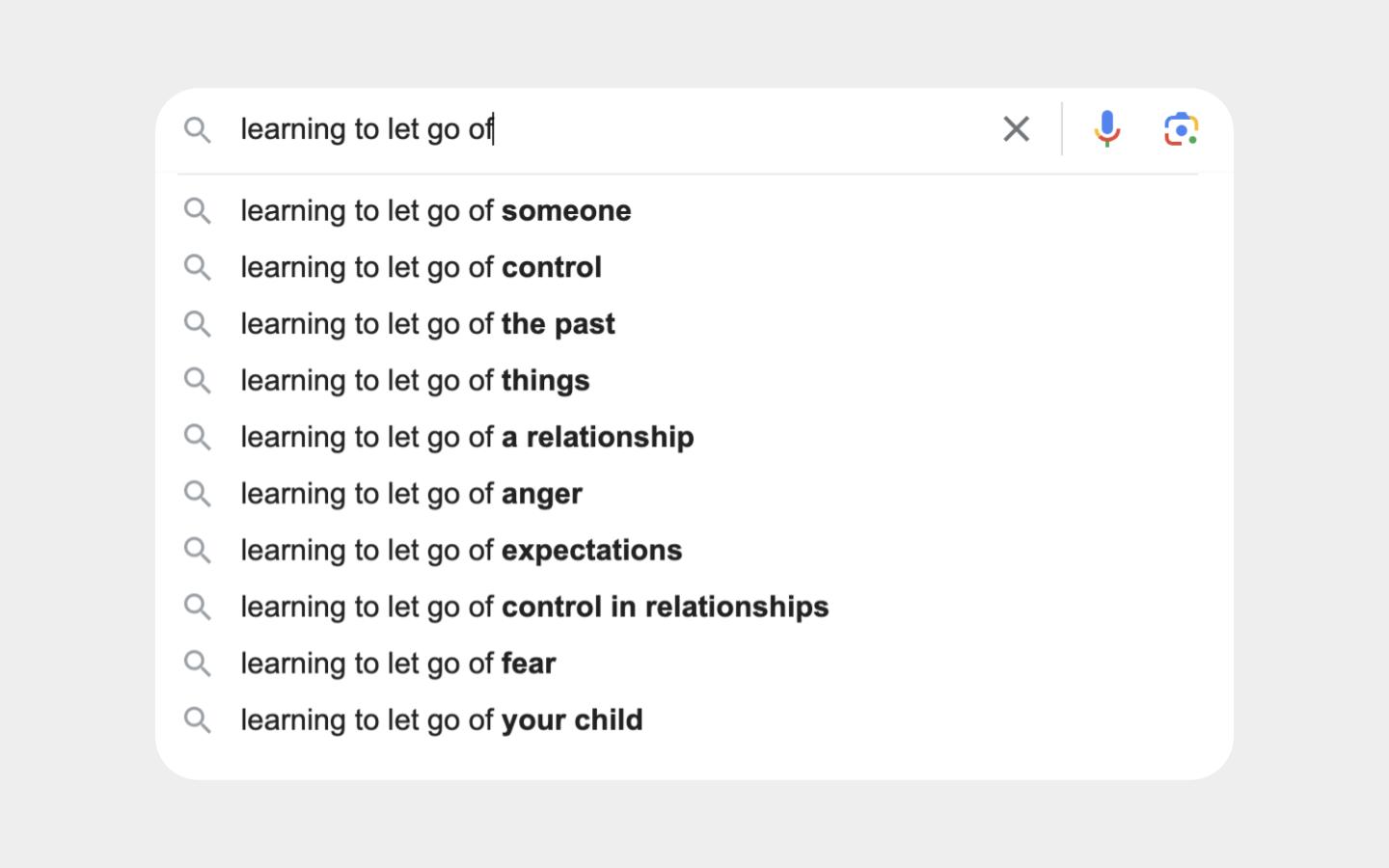

Finally, Anne-Laure Le Cunff’s “The Science of Learning to Let Go” is one of those pieces I’m still thinking about a month after reading.

(If you like that, and want something short enough to carry with you forever, contemplate Tilopa’s Six Nails.)

Books

Mike Rother posted a thing that included a citation from Ignorance and Surprise: Science, Society, and Ecological Design by Matthias Gross and I immediately picked up a copy. (Ever since I encountered one of the key concepts of my consulting practice in a tossed-off back page column about fish scientists in a 1995 ecology journal, I know to pay attention to these people (ecologists).)

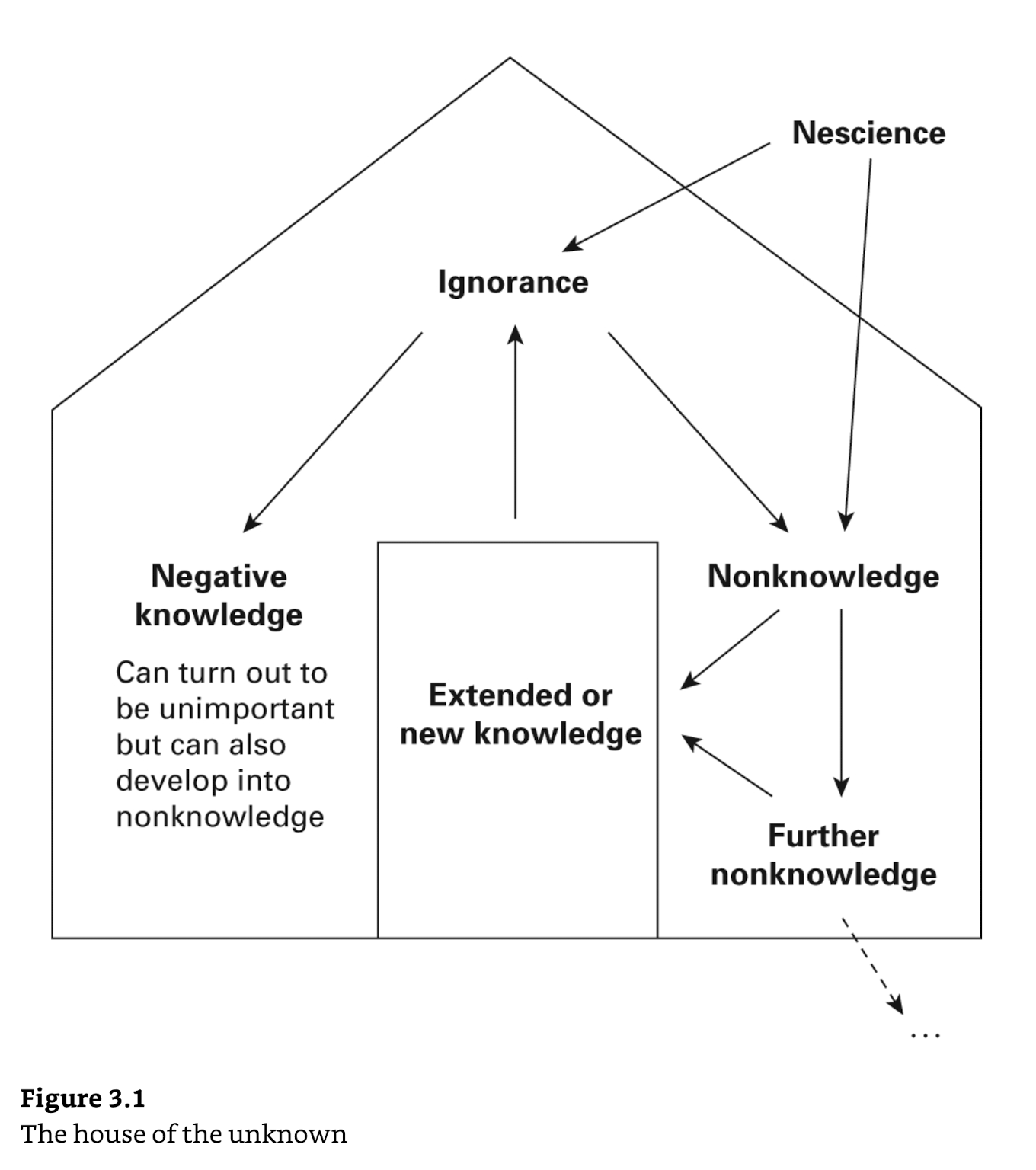

I owe Mike and his outfit more detailed notes on this book, but for the moment let me share this amazing illustration. I give you the “house of the unknown” ↓

The ecological interventions (or experiments) Gross is concerned with tend to happen in “the real world” instead of a laboratory. And that’s the ledge I use to climb up into this book. Kaizen is the choreography that happens in order to allow people to make improvements to their own “real world” work and relations. I think we can learn a lot from this book’s framework about how people respond to various kinds of surprising conditions or discoveries.

On the site

Recent changes @ improvesomething.today:

- Added to the Junk Drawer → a placeholder for LinkedIn carousel postings I’ve been doing. These mostly reiterate items from the site, but in a format people seem to enjoy.

- Some changes to e-mail newsletter delivery, formatting, and list membership that hopefully go smoothly. (If you’d like to join, unsubscribe, or change delivery of the e-mail newsletter, this is the link.)

Course recommendation

I recommend The Center for Humane Technology’s free, self-paced, multi-mode course, “Foundations of Humane Technology.”

If you design or make decisions about technology products or experiences, you might take a couple of afternoons to work through this material. The shift you’ll grapple with:

And the course:

Monthly links & notes for November 2023

This month: 4 articles & an online course.

Online reading

First, a remembrance of Freddy Ballé—the French popularizer of lean—after his passing last month. You may know his name from a few of the books he cowrote with his son, Michael Ballé. Dan Jones writes:

I can still hear his voice saying, “Keep your focus on the detail of the work and understand its significance for the customer and the system as a whole.” Thank you, Freddy, for your example and your inspiration.

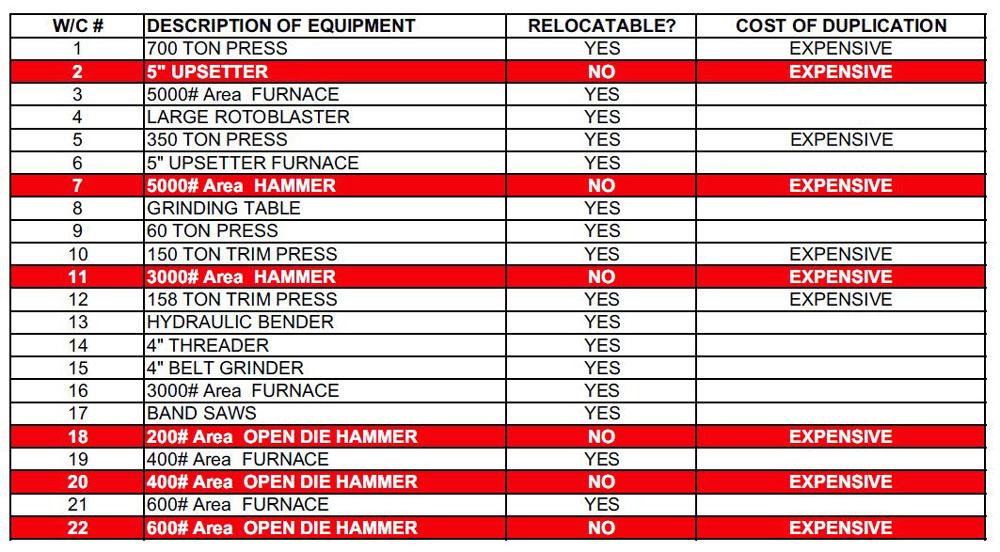

Product-Quantity-Routing (PQR) Analysis and its close cousin, Work Unit Routing Analysis (WURA), are super underutilized continuous improvement methods for discovery and group sense-making and generally sorting things out. I’ve used WURA a bunch recently in my client work, and would like to write it up here soon. In the meantime, I am curious about how other people use PQR. Shahrukh Irani had this to say, in a very detailed post:

Kaizen event teams usually don’t have time to collect relevant data for all products. But with analyses already complete, the team could easily use just the PQ Analysis to segment their product mix into at least two areas, high volume and low volume. Then, using the PR Analysis for at least the high-volume segment, they could seek product families in that segment. Any product family found in that segment could then be the focus of a high-impact kaizen to implement a cell.

We’re now a solid year into the impossibly tedious and generally underwhelming LLM/spicy autocomplete/ChatGPT era. Looking past the OpenAI+Microsoft clownshow currently underway, two things are clear:

- These LLMs aren’t actually good enough to use for anything besides some Cal Newport style deeply evil “Deep Work” (aka middle-management strivers getting ahead by pushing lower status work onto lower status people in/outside an organization); and

- They waste too much water.

I’d encountered that second point repeatedly, but not really understood it until I read this, by Manuel Pascual in El País:

Many data centers use cooling towers to prevent overheating, the same system used in other industries. It is based on exposing a flow of water to a current of air in a heat exchanger, so that the evaporation cools the circuits.

This method is more energy efficient than electric coolers, but it involves a significant amount of water evaporating (i.e. not returning to the circuit). Approximately 20% of the water used in cooling systems (that which does not evaporate) is discharged at the end of the cycle into wastewater treatment plants. “This water contains large amounts of minerals and salt, so it cannot be used for human consumption without being treated first.”

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/C3Q5BCDTHJEJXFBKBJQHGGZMUA.jpeg)

(Thanks Bill for passing that link along.)

Finally, all the chatter about spicy autocompletes “ruining” software development brought to mind one of my favorite pieces of online writing—Ellen Ullman’s 1998 two-part essay “The dumbing-down of programming.”

The computer was suddenly revealed as palimpsest. The machine that is everywhere hailed as the very incarnation of the new had revealed itself to be not so new after all, but a series of skins, layer on layer, winding around the messy, evolving idea of the computing machine. Under Windows was DOS; under DOS, BASIC; and under them both the date of its origins recorded like a birth memory. Here was the very opposite of the authoritative, all-knowing system with its pretty screenful of icons. Here was the antidote to Microsoft's many protections. The mere impulse toward Linux had led me into an act of desktop archaeology. And down under all those piles of stuff, the secret was written: We build our computers the way we build our cities—over time, without a plan, on top of ruins.

My Computer. This is the face offered to the world by the other machines in the office. My Computer. I've always hated this icon – its insulting, infantilizing tone. Even if you change the name, the damage is done: It's how you've been encouraged to think of the system. My Computer. My Documents. Baby names. My world, mine, mine, mine.

Read “The dumbing-down of programming” part 1 and part 2.

On the site

Recent changes @ improvesomething.today:

- I culled books from the reading list (eventually I’ll add new ones), and

- switched the site appearance from Ghost’s previous/old default theme to its current/new default theme.

Course recommendation

This season I’m luxuriating in an online, affordable, six-week information architecture course with Dan Klyn and a few new learning friends. Now, I first studied information architecture back in grad school, in a course taught by Dan in 2006 or so. It’s awesome to revisit this way of apprehending and creating environments more than 15 years later, and to do so with one of the people who have really pushed/pulled the discipline forwards. This is absolutely a course you should consider taking in 2024.

Monthly links & notes for October 2023

3 articles, a case study, 2 books & an upcoming event.

Trying something slightly different today: sharing a couple online reads, interesting books, and other recent updates. I might end up doing this monthly.

Online reading

First, this great short article from the great Donald Wheeler:

“Adjustments are necessary because of variation. And the variation in your process outcomes doesn’t come from your controlled process inputs. Rather, it comes from those cause-and-effect relationships that you don’t control. This is why it’s a low-payback strategy to seek to reduce variation by experimenting with the controlled process inputs. To reduce process variation, and thereby reduce the need for adjustments, we must understand which of the uncontrolled causes have dominant effects upon our process.”

Next, Mandy Brown wrote about work being too much and also not enough:

“Once you accept (or re-accept) that there is too much, it becomes easier to turn some things away. You may still feel grief or loss at the things you cannot do. You may feel guilt, especially if an institution or person benefits from you feeling that way. But accepting that you must leave some things undone shifts the problem from one of being not enough to one of being in a position to make choices. And even when those choices are coupled to difficult or prickly constraints, they are still choices.”

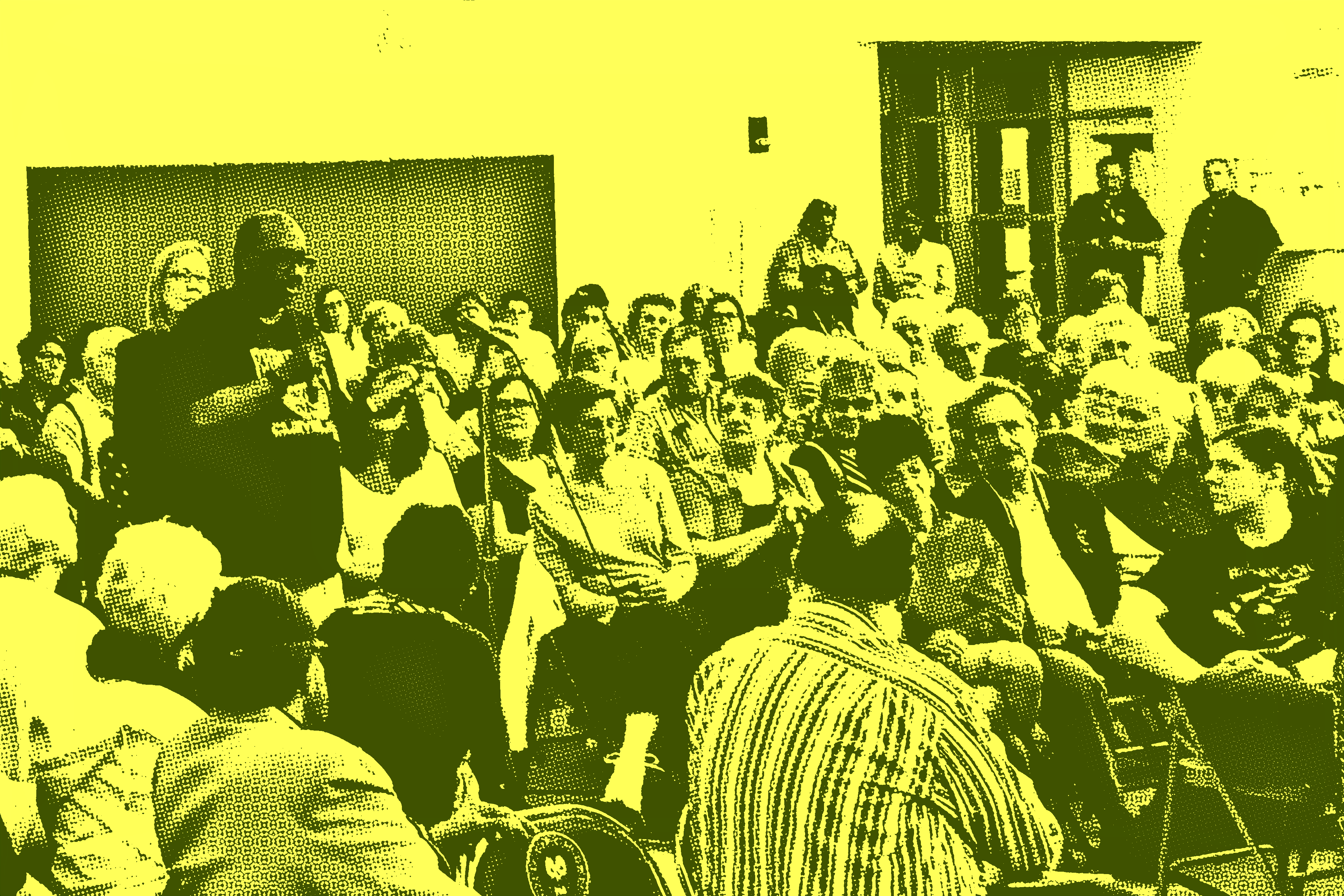

Here’s a fun one—this case study by Regina de Melo on a lean project I designed and contributed to several years ago:

“By piloting small and fast ideas and using agreed-upon measures of success, ideas are vetted quickly and objectively by reviewing the attainment of the agreed upon outcomes.”

Lots of specifics about outcomes and trade-offs we encountered during this engagement. I enjoy this because the consulting team (that’s me!) recedes into the background and, as far as I’m concerned, that’s as it should be.

And this, on the topic of listening as a capability for movement-building, from Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba in the Boston Review:

“Organizers will often repeat the maxim, ‘We have to meet people where they are at.’ It is difficult to meet someone where they’re at when you do not know where they are. Until you have heard someone out, you do not know where they are, so how could you hope to meet them there? Relationships are not built through presumption or through the deployment of tropes or stereotypes. We must understand people as having their own unique experiences, traumas, struggles, ideas, and motivations that will inform how they show up to organizing spaces.”

Books

I’m still hung up on Naomi Klein’s “Doppelganger”—this will end up being my favorite book of the year unless something truly amazing happens. Read it. It is somewhat unclassifiable (memoir? polemic? weird-as-hell COVID-19 retrospective? etc.?) but whatever it is, it is an astonishment. If you need more information, start with Cory Doctorow’s review.

Beyond that, I am increasingly impatiently waiting for my preorder of “The Flow System Playbook” from Turner and Thurlow to get in.

“The Flow System” is an invaluable book—several of my projects have cribbed heavily from its pages—but I think the playbook format will really adhere to Thurlow’s strengths. More about this one after I dig in.

On the site

Recent changes @ improvesomething.today:

- I added a links & listens page with selected continuous improvement blogs and podcasts (only the weird/good ones),

- refreshed a couple recommended books on my reading list, and

- updated about this site with more information about your privacy and additional ways of reading.

As the algorithm-poisoned social media landscape decoheres, I am left feeling that web sites are great. I wish there were more of them. So I try to keep this one tidy.

An upcoming event

Makesensemess—the “nerdiest party of the year”—is coming up in a few weeks and I would be delighted to see you there. It’s a two-hour, cheap, online celebration of things people do to make sense of an absurd and silent world. Last year’s Makesensemess was phenomenal.

That’s it for now! Have an awesome day.

Dan’s Device: “Now that I see it… [it’s completely wrong.]”

![Dan’s Device: “Now that I see it… [it’s completely wrong.]”](/content/images/2024/08/IMG_6240-1.jpeg)

After “now that I see it” come words you need to hear as early as possible.

It is 1976. Neil Diamond saunters onstage at The Last Waltz and introduces his performance of ‘Dry Your Eyes’ by saying:

I’m going to do one song for you, but I’m going to do it good.

Isn’t that what we all want? We want to do something once, and to do it good. And easy enough: the first step is to be Neil Diamond.

The rest of us should probably acknowledge that—whatever the work is—we’ll have to do it more than once, because it almost certainly won’t be done good the first time.

My friend Dan gave me the notion of the now-that-I-see-it moment. This occurs when a work-in-progress becomes real enough that people can say a sentence beginning with “Now that I see it” and ending with things like “it’s completely wrong” or “we forgot this important detail” or “this will never work for this particular reason.”

Methods for building quality at the source, shifting left, set-based design, and so forth all help elicit “now that I see it” moments as early as possible.

By arriving earlier to “now that I see it,” we also arrive earlier to the wrong place, to the just-revealed insight, or to the key constraint. It is hopefully early enough that there is wiggle room to learn and iterate and retry.

Airbrushing the side of a van is delightful. It is a job that takes as much time as you care to give. But you need only outline those first few flames and/or wolves to wedge open space for the objection that what we really need is a bicycle, or for the idea that we might be able to take the train.

I leave you with this dismal little project management couplet:

“Now that I see it” is certainly true;

That’s why to use tape first & then glue.

(This advice does not apply to Neil Diamond or to his beaded shirts.)

Noticing little things & little thinks

Noticing at work. Noticing on the cushion. And noticing while out & about. These three are related. I am still figuring out how.

I’ve written about the power of noticing before:

- noticing why people resist change,

- noticing as a bedrock practice of lean, and

- noticing as a way to close meetings.

Beyond all this, I spend a certain amount of time and effort on a meditation cushion, where mental noting has been a tremendous relief and balm over the years. Briefly, mental noting is a practice of noticing and ‘tagging’— without discussion or judgement—sensations and thoughts as they arise.

Capability and joy come through seeing things with a little less presumption, a little less judgement, and a little less hurry towards sense-making.

Noticing while out and about

A great way to try different ways of seeing and experiencing is to play some of the games in Rob Walker’s The Art of Noticing. One example is the “secret scavenger hunt” of looking for security cameras while running an errand: which cameras want to be seen?—and which want to remain hidden?

The ant’s puzzle

How is observing the bottoms of coffee mugs (a Rob Walker staple) similar to looking carefully for those places where workplace environments produce errors, injury, and waste?

And what do both of these have in common with the experience of sitting quietly for a moment and paying careful attention to the quantity of thoughts that arise unbidden and just as quickly fall away?

I don’t have a tidy answer. I wish I did.

I can see that these three are related somehow, meaningfully. It is as if they were three legs of a stool that I—as an ant—endlessly crawl to and fro and back to, without apprehending the larger structure. I will keep trying, and I encourage you to give it a go as well.